For teens across the country, their eighteenth birthday is a major milestone – as these children reach the age of majority, they find that suddenly they can call themselves adults. As discussed in the previous article, “Help Needed For Youth Aging Out Of Foster Care In America,” for 23,000 US teens aging out of foster care each year, crossing the threshold into adulthood often comes with challenges and responsibilities. These adults-by-law are still vulnerable youth who have a lot of learning to do, but without the support structures that other youth outside of the child welfare system have, it can become easy for them to lose their way.

Increasingly, states are moving to raise the age limit for children in foster care in order to help them maintain the systems of support they need to succeed after they turn eighteen. As child welfare systems across the country continually update their ideas and infrastructure to provide positive outcomes, there is a debate over how money should be invested. How much, exactly, does it affect foster care costs when a child is not adopted?

Using a cost-benefit analysis technique that averages together costs of various life outcomes (i.e. the average cost of a child born to a mother under 21, the average cost of detaining a prisoner, the average cost of medical fees for victims of abuse, etc.) to arrive at effective foster care costs for allowing those outcomes to occur, the Jim Casey Youth Opportunity Initiative’s (JCYOI) 2013 estimates, it cost the United States roughly $300,000 per child that aged out of the foster care system. With the 26,000 children that aged out that year, the total expense for the nation was about $7.8 billion. With so much money on the line and states trying to remain fiscally responsible while still helping these children in need, how can they reduce costs while improving outcomes for youth?

Foster Care Costs for Unadopted Youth

According to the latest study, a 2011 report from the National Council for Adoption (NCA), it cost roughly $19,107 per child per year for foster care maintenance payments (foster care stipends paid out to foster parents), and $6,675 per child per year to pay for the administration of the child welfare system at that time. This means that the total cost per child per year was about $25,000. By contrast however, their study shows that subsidized adoption payments averaged $8,435 per child per year and the cost of “arranging and monitoring subsidized foster care adoptions” was about $1,867 per child per year, bringing the total cost to the government of a subsidized adopted child in 2011 to around $10,000. This represents a foster care cost savings of nearly 60% – it is less than half as expensive to subsidize an adoption than it is to allow that child to remain in foster care.

How Does Subsidized Adoption Save on Foster Care Costs?

It’s important to understand what “savings” means in the context of this cost-benefit analysis of foster care costs. The estimates used to determine such costs examine two scenarios: the cost of a subsidized adoption and the associated outcomes compared to the cost of supporting someone who experiences the negative outcomes associated with those who left the foster care system. For each negative outcome, a cost can be associated – whether it’s due to government assistance, medical bills, cost of incarceration, income differentials between education levels, etc. – if there is more money spent on a person who has suffered negative outcomes than one who experienced positive outcomes due to preventative measures (i.e. subsidized adoption or an increased foster care age limit), it naturally makes sense to spend that money to prevent those negative outcomes instead of paying for them as they occur.

The NCA reports that, children adopted from foster care are “three times as likely to be in a financially secure household,” and that they are more likely to live in a safe and supportive neighborhood. Continuing, the study mentions that two-parent families, higher parent education and income level, and a safe and family-friendly neighborhood are “associated with more favorable outcomes for children and youth.” They conclude that subsidized adoptions help to lessen the foster care costs on taxpayer funded entities like the public school system, child welfare and social welfare agencies as well as the criminal justice system, while providing more stable futures for former foster youth.

Age Limits Affect How Much Foster Care Costs

As reported previously in the article, “Help Needed For Youth Aging Out Of Foster Care In America,” more than half of the states in America are already implementing increased age limits for foster children. Given that the cost of subsidized adoptions is so much cheaper than maintaining a child in foster care, it may seem as though extending foster care would be a costly choice. While this is true, it is becoming increasingly evident that when youth in care have extended services that can help them through post-secondary education, the positive outcomes they experience mean that it is more cost-effective than allowing them to age out into a world they’re unprepared for. But how, exactly, are states addressing the needs of their youth as they cross the threshold into adulthood?

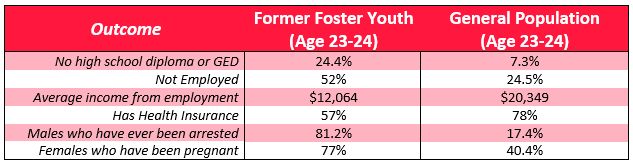

As with subsidized adoptions, it’s beneficial to examine the negative outcomes often associated with time in the child welfare system relative to the general population. The National Resource Center for Permanency and Family Connections (NRCPFC) provided the following chart describing how at-risk foster youth are for various negative outcomes compared to the youth in general:

By the time they’re 25, former foster youth are nearly 3 times less likely to get their high school diploma, half as likely to have a job and will earn roughly 40% less than their peers who have not been in foster care. According to the NCA, after calculating the average lifetime earnings (from age 20 to age 65) of people across three different levels of education, there are literally billions of dollars in foster care costs savings to taxpayers correlated with people who attained a higher education level – but why?

How Does Extending Age Limits Decrease Foster Care Costs?

Alongside the other negative outcomes of homelessness, early pregnancy, incarceration and less education, 25% of former foster youth who aged out of care “will have experienced post-traumatic stress disorder at twice the rate of United States war veterans.” While the NRCPFC reported on women aged 23 to 24, the NCA finds that 71% of women who aged out of foster care will be pregnant by age 21. In fact, the NCA finds that only 58% of children in foster care will graduate high school by age 19, in contrast with 87% of all 19-year-olds. The risk of negative outcomes starts well before these youth legally become adults and follows them into adulthood. With just three extra years of support through the child welfare system, as the NRCPFC suggests, these risk factors can be addressed:

“Extending foster care has substantial financial benefits to both youth transitioning out of care and to society. Allowing young people to remain in care until age 21 doubles the percentage who earn a college degree from 10.2% to 20.4%, thereby increasing their potential earnings. Researchers project that a young person formerly in foster care can expect to earn $481,000 more over their work life with a college degree than with only a high school diploma (Dworsky, 2009). A cost benefit analysis conducted in California found that increasing attainment of a bachelor’s degree would return $2.40 for each dollar spent on extended foster care from ages 18 to 21 (Courtney et al., 2009).”

These results come in part from what is known as “The Midwest Study” – a study by Mark Courtney and Susan Dreyfus – that compared the outcomes of nearly 700 youth who aged out in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Illinois; The age of emancipation is 18 in Wisconsin and Iowa, but 21 in Illinois. The increased age limit in Illinois meant that former foster youth were four times more likely to attend college by 21 and that the rate of pregnancy amongst women formerly in foster care dropped by around 38%.

What’s the Age Limit?

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), 25 states and the District of Columbia have extended the foster care age limit past 18. Below is a map that details which states have extended the age limit using the Title IV-E funds that were made available for that purpose with the Fostering Connections Act of 2008.

Please note that this image does NOT indicate that a state doesn’t provide support to youth past age 18 – it speaks mostly to the states that offset these aging-out related foster care costs by making use of the Title IV-E federal funds dedicated to this purpose.

New Jersey, for instance, supports its foster youth up until age 21 through the use of funding from the John Chafee Foster Care Independence Act, which replaced the Independent Living Program originally built into the Title IV-E funds. Introduced in 1999, the Foster Care Independence Act offset states’ foster care costs by increasing funding for states to test and develop programs for youth transitioning out of care. Technically, although a youth “ages out” at age 18 in New Jersey, they are free to leave their case open provided they meet the basic requirements (they’re not an adjudicated delinquent or detained in a detention facility). These are the programs available to foster youth in New Jersey until they turn 21:

- Aftercare – A contracted agency provides “intensive case management and support services for adolescents aging out.” They work to help youth obtain meaningful employment, housing, college tuition, and access to Chafee Wraparound Funds (funds provided specifically to youth in aging-out support programs to help cover security deposits, rent, furniture, driving lessons and other basic essentials for adulthood). Available from ages 18-21.

- Life Skills Training – A contracted agency helps adolescents develop the skills needed to transition to independent living from foster care. Available from ages 14-21.

- Transitional Living – An up-to-18-month housing program that provides a safe housing, case management, life skills, counseling and more. Available from ages 16-21.

- Youth Supported Housing – A contracted agency provides services similar to the Transitional Living program, but with potential for a flexible timetable as youth are encouraged to stay until they feel ready. Available from ages 18-21.

- New Jersey Foster Care Scholars – The New Jersey Foster Care (NJFC) Scholars program is a state and federally funded program that provides eligible adolescents, with a history in care or with homelessness, funding towards tuition and fees, room & board or educational supports while pursuing a post-secondary education. Available from ages 16-23.

In addition, since so many of the risk factors associated with negative outcomes begin well before a child ages out, New Jersey requires that caseworkers perform a life skills assessment when a child turns 14. This assessment, the Ansell Casey Life Skills Assessment, allows the caseworker and the family management team to adequately understand how well prepared a youth will be as their time in foster care comes to an end.

Although seemingly expensive, an increased age limit on foster care is proving more and more successful at providing not only better outcomes for the youth served by child welfare agencies across the country but also at improving the efficiency of taxpayer dollars. It is becoming increasingly apparent that by limiting foster care to age 18, states are investing into a system that only further compounds intrinsic risk factors for the youth in care. With more than half of the states in the nation having already raised the age limit and with others, like New Jersey, providing services well beyond a child’s 18th birthday, the United States is trending towards more positive outcomes for our youth and a better, more efficient child welfare system with fewer foster care costs.

For more information about any of the New Jersey programs listed above, please visit: http://www.state.nj.us/dcf/policy_manuals/CPP-VI-B-1-300_issuance.shtml

If you are not in New Jersey, but would like to learn more about your state’s age limit, please visit the following link and scroll down to the searchable table of State Laws: http://www.ncsl.org/research/human-services/extending-foster-care-to-18.aspx

Yes, as the needs grow greater for kids aging out of foster care so should the age. I have been working with kids who have aged out and are still in need of services of some support but mainly permanent connections. Those connections support the young person who has experience trauma due to being in foster care. its that one connection that will influence change towards their well being. Also those supports of services maybe the only connection that a child has.

Poor people loose parental rights over things rich people don’t. A woman who lost a child to adoption for a petty theft or drug offense won’t be allowed to keep her next child if she’s on welfare but will be allowed to keep her next child if she’s married to someone who has a job or has a job herself. The right of a child to their own parent’s care should never be extinguished and the state should not have the purview to adopt out the children it it’s care. Termination of parental rights should not mean the termination of the rights of their sons and daughters. Adoption strips the son or daughter of their rights where foster care does not. Foster care provides oversight of the people in care whereas adoption does not. Kids are safer in foster care than being adopted.

Age 18 is a joke. Bio kids aren’t ready at 18 and kids in foster care are even less ready. Some will not have graduated yet from high school. It is a backwards system that rewards kids NOT to get adopted just so they and their parents can be sure they have enough to support them through those critical young adult years. Most children aren’t truely independent until 22-23 years. It needs to be extended to save both on long term costs to society and to promote adoption of pre-teen and older children (ie those ages 10-15).

it is nice to read positive and workable statistics that only make sense once you read the analysis of the outcomes. Extending Foster Care to age 21 is a GREAT AND WORKABLE CONCEPT that tremendously benefits the Foster Youth and sets them up to a MORE SUCCESSFUL AND PROMISING ADULTHOOD! I only wish that the states that have yet to extend foster care beyond age 18 will HURRY UP AND DO IT! Everybody wins when foster care is extended an additional 3 years and those states that haven’t done it yet are greatly impeding the lives of those who age out at age 18… Too many bad things happen when foster kids age out at 18 and hopefully extending foster care beyond 18 will eventually become a mandatory and common event among the 50 states and Washington, D.C. and hopefully the sooner the better for all of us!!! Thank You!