According to the LA Times, Los Angeles community colleges, roughly 44,000 students are struggling with homelessness. Housing costs for students are a problem across the nation, but for foster youth the crisis can be made worse if they are not adopted or their foster families are not supportive.

Reporting on the issue, the LA Times spoke with former foster youth Myriah Smiley, 19, who had her food stamp supply cut off when she received a welfare check. Forced to resort to couch surfing as she studies and dreams of opening her own bakery, Smiley said she’s often forced to go hungry: “I cry at night and hope for better days.” Smiley’s story is not an unusual one; according to a University of Wisconsin Hope lab study, 29% of former foster youth attending community college nationally are homeless.

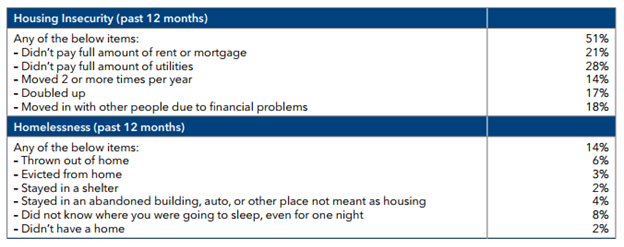

It’s important when speaking about homelessness to understand how it is defined. Although the word “homeless” might evoke images of a person in tattered clothes huddled up against a wall on a city street, the students in question don’t fit the stereotype which lowers the visibility of their plight in public. This is because there are concrete metrics by which homelessness can be defined and measured and they have little to do with one’s appearance. The University of Wisconsin Hope lab defines homelessness as being “without a place to live, often residing in a shelter, an automobile, an abandoned building or outside.” Related to this concept but distinct in its own right is the notion of “housing insecurity,” which the study defines as “a broader set of challenges such as the inability to pay rent or utilities or the need to move frequently.” A high degree of housing insecurity can often lead to homelessness.

What’s perhaps most alarming is that the students struggling with these issues lack the basic support structure to allow them to properly focus on their studies and succeed. 51% of the Wisconsin University Hope lab study respondents expressed some degree of housing insecurity, and a full 14% of them were considered homeless. To give some more insight into the specific factors that make a person housing insecure or homeless, here’s an excerpt from a table in the study:

Although not all of the survey respondents were in foster care, it’s important to note once again that of former foster youth enrolled in community college, 29% were homeless. In a white paper by the Congressional Hispanic Caucus Institute, Sara Garcia writes that, “Students who are concerned about where they will sleep that night are ill suited to complete their course work.” Nationally, only 2% of foster youth graduate college – housing insecurity and homelessness are two of the obstacles that lead to this low graduation rate. Furthermore, as Garcia reports, obstacles persist in spite of sincere attempts on the part of these youth to improve their situation: “Many homeless and foster youth report working full time in order to cover college costs; however, full- or part-time employment takes time away from academic studies and can infringe upon the students’ ability to study or complete assignments. As a result, their grades suffer.” According to the University of Wisconsin Hope labs study, homeless students were more likely than housing-secure students to work more than 20 hours a week but were half as likely to earn $15 per hour. As they work more and earn less, students find themselves unable to properly continue their studies: “…homeless students spent more time commuting, less time sleeping, and more time caring for other adults….”

But how can states work to help these students?

A study from the University of Chicago examined 700 foster children in three states and found that when foster youth received continued support from the child welfare system through the age of 21, their success rates improved. According to Michael Winerip of The New York Times, “The foster children from Illinois, which has long allowed young people to remain in care until their 21st birthday, were more likely to have completed at least one year of college than their counterparts from Iowa or Wisconsin, where the age of emancipation at the time was 18.” This proves a critical point – when a youth exits the child welfare system without being adopted but wishes to pursue post-secondary education, they still require support structures to help them succeed. In line with these observations, a new piece of federal legislation was proposed in November of 2016 aimed at removing a number of obstacles facing the housing-insecure and homeless foster youth in our nation’s schools: The Higher Education Access and Success for Homeless and Foster Youth Act of 2015 (HEASHFY Act).

According to an article from Diverse, some of the policy changes include allowing homeless-identified youth under 24 to be classified as independent students (which allows them to get full financial aid), streamlining the FAFSA paperwork that involves identifying one’s self as homeless and removing the requirement that students must have their housing status re-verified ever year. In another big step, the bill would also provide in-state tuition rates for foster youth and ensure that the services these youth use to survive won’t count against their potential financial aid for being considered income.

Part of alleviating this burden is identifying homelessness as early as possible. If a student’s housing security can be identified quickly, it’s more likely that their state’s child welfare agency will be able to help them and prevent their homelessness from interfering with their education. The Institute for Children, Poverty & Homelessness has put out a state-by-state ranking that details how well states identify the housing security of their students from pre-kindergarten all the way up to graduation. The best and worst performers are:

Top 5 States – Identifying Homeless Students

1) Oregon

2) New York

3) Alaska

4) District of Columbia

5) Vermont

Bottom 5 States – Identifying Homeless Students

47) Alabama

48) New Jersey

49) Connecticut

50) Tennessee

51) Mississippi

You can view the full chart here.

The success of foster youth in their post-secondary education depends heavily on the supports they receive after they graduate high school. If homeless youth are to be helped, states will need to make sure they both increase the support structures for homeless students and identify those students as soon as possible.

For its part, New Jersey has joined Illinois and a number of other states in raising the age a youth may remain in foster care up to 21. Furthermore, there are two ways that homeless students can get help finding housing – either through the Adolescent Housing Hub (AHH) or the New Jersey Foster Care (NJFC) Scholar Gap Housing Program. The AHH is a non-emergency housing platform that connects homeless youth with a number of housing options. The service combs through their list of housing programs and matches a given youth with the top three choices given the specifics of their case history. It’s intended to serve as a long-term housing option which will eventually guide the youth to a more permanent residence.

The Gap Housing Program is limited to NJFC Scholars in good standing with their institution. The program is aimed specifically at helping students find housing for the gap months between school years and during the winter break. As many colleges don’t let their students remain on campus while school is out and a number of foster youth have no place to go, this is a vital service that helps a number of NJFC Scholars retain the housing security they need to focus on their studies.

For more information on the Adolescent Housing Hub, please visit: http://www.performcarenj.org/youth/resources/adolescent-housing-hub.aspx

For information on the Gap Housing Program, contact FAFS’ Director of Scholarship, Marjie Blicharz, at mblicharz@fafsonline.org

To learn about housing initiatives nationally, please visit: https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/outofhome/independent/support/housing/