Congregate Care: The Case for Closure

Some believe that group homes and congregate care in general provide only a band-aid for a bigger problem. Though they do provide a necessary service, they are increasingly seen by child welfare agencies as an inadequate solution to the issues facing the national child welfare system. Aside from the fact that regulation varies from state to state (resulting in large differences in the handling of such facilities), group homes and Residential Treatment Centers (RTCs) often put children at a great distance from their families.

One such group home employed by the state of New Jersey, Devereux, is actually located in Florida. Judge David Bazelon with the Center for Mental Health Law, writes:

“…far too many children are placed at a great distance from their homes. For example, most District of Columbia children in RTCs are placed outside the District—many as far away as Utah and Minnesota. Many families, especially those with limited means, find it impossible to have any meaningful visitation with their children.”

Bazelon continues on to suggest that although it is accepted that children do best in close proximity to their families and with consistent parenting, many governments still rely on distant, out-of-state facilities. To further complicate the problem, residential treatment centers are “inherently artificial” environments, where the child is unlikely to encounter any of the behavior triggers one might encounter outside of an institution. In a bleak reminder of the consistent care that children require, Bazelon goes on to cite a study that shows nearly 50% of children in an RTC get readmitted, and “75% were either re-institutionalized or arrested.”

Becoming Obsolete

Like some children, Jacque Mata-Lemons, a former foster child and group home resident, feels that group homes are too institutional and cold: “A lot of the kids compared it to a prison,” she said, speaking of what she believed to be extreme restrictions on internet, TV and other things that many kids use to normalize their lives. In an institutional setting, it can be difficult to administer individual care, and the setting itself suggests a lack of normalcy to the children. Of course, one must ask where these children would go if not for one of the myriad options within congregate care. Mata-Lemons does not believe that the complete elimination is really possible due to the difficulty of finding qualified foster parents: “They should have group homes, but they need to have laws to make sure the kids can feel like normal kids.”

In spite of the necessity to employ these placement options, many states believe it is clear that group homes and RTCs represent only a partial, temporary solution to the needs of the foster care system. Like their ancestor the orphanage, congregate care facilities are starting to become obsolete and, in some cases, unhelpful. Unfortunately, their absence could complicate the future of foster care.

In California, after group homes came under criticism, lawmakers drafted a 56-page reform aimed not only at increased oversight for group homes but also at increasing the recruitment efforts of new foster families. Meanwhile, at the close of 2015, Tulsa closed two of its state-run emergency children’s shelters in an effort to revamp the foster care system. As with California, the hope is that foster children will find forever families, not facilities, within which they can thrive and be cared for.

New Jersey’s Progress

For New Jersey’s part, the state has been slowly and steadily phasing out the out-of-home placement options in favor of kinship care placements, which place children with a relative or close family friend instead of a group home, treatment center or typical foster parent’s home. In an analysis of the aforementioned Commissioner’s Monthly Reports from 2014, 2015 and 2016, Foster and Adoptive Family Services found that overall, out-of-home placements have been on the decline.

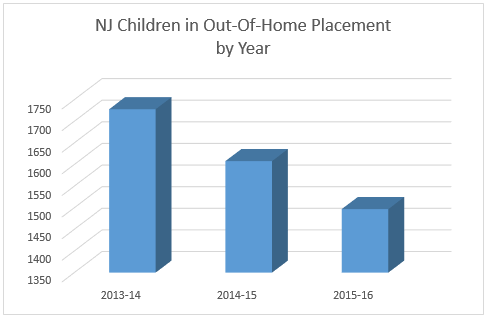

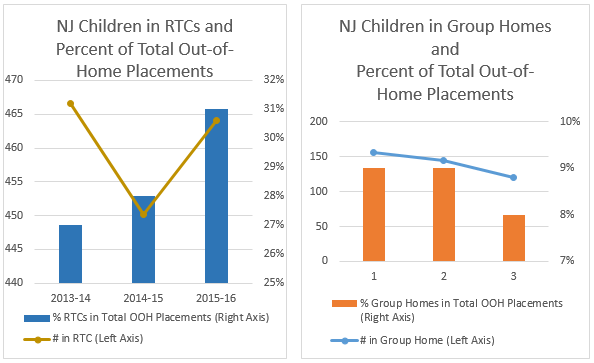

This chart, developed from the three reports, shows the total number of children in out-of-home placements for each of the past three years. By 2016, the total number of children in such placements was 1497, a drop of 231 from the 2013-2014 year. Furthermore, although residential treatment centers and group homes represented a combined 10% of total foster care placements and 39% of out-of-home placements, the actual number of children using the options has declined, as shown in the next two graphs:

Moving Foster Care Forward

The decline of congregate care usage across the nation is being met with mixed emotion, from concern over what to do with incoming foster children to excitement over positive reform. Speaking to the Christian Science Monitor, Children’s Village CEO Jeremy Kohomban said, “The longer kids stay in institutions, the less capable they are of reintegrating into society. We need to use the residential system as a short-term emergency room, then get kids back to the community.” Reporting for Propublica.com about California’s reforms, Joaquin Sapien writes, “The idea is that if the state can find such families, fewer children will need to enter the group care system to begin with.”

For all the reasons stated above, congregate care seems less and less viable as a long-term option for foster care. David Crary of the Associated Press, writing about the phasing out of group homes across the nation, has said that there is “a growing consensus within the child-welfare field that institutional settings for foster children – while sometimes necessary – should be used sparingly.” In a move that gives weight to Crary’s observation, Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) drafted legislation in 2014 to eliminate federal funding for long-term congregate care. Organizations which operated group homes, such as Children’s Village, are also taking steps to move away from congregate care. Their new model involves a goal of no more than a six month stay in their group home facilities and is paired with several other programs aimed at keeping kids in families.

They’ve also worked to find foster families or relatives for children, going so far as to employ private investigators in some cases, and have opened up the WAY Home care transition program to children (and their families) for five years after their initial placement with Children’s Village. The message from professionals all around the country is clear: congregate care needs to be reviewed and reformed.

Finding Forever Families

As the nation moves forward in its efforts to improve the lives of displaced youths and families damaged by violence or drug abuse, it is important to remember that the best way to help out is to care for a child. In this spirit, Kathleen Burns of the Oklahoma Department of Human Services has a message for everyone considering a life of fostering children: “We need more foster parents, period. We need people who are open-minded and will take teens, kids with developmental disabilities and sibling groups.”

Though the United States has come a long way from the time of grass-stained, soot-covered orphans under the control of a mean old woman, it is the consensus within the child welfare field that the group home and congregate care philosophy should be reshaped with a new goal in mind. Instead of simply finding children a place to live, the foster care system should constantly and continually support children and parents in the search for a forever family who can give the adequate, individualized support and love that all children deserve.