Although unintended, deportation often results in the children of undocumented immigrants being placed into the foster care system.

The Cost of Deportation

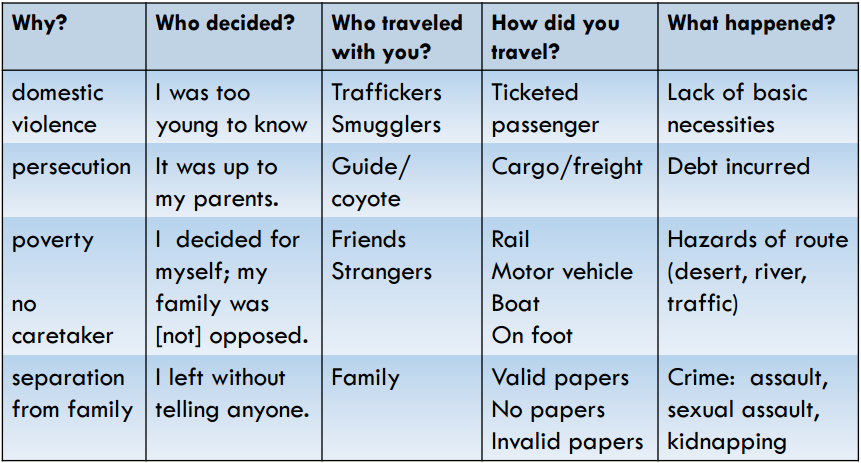

This table shows a snapshot of some ways children may enter the country. (New Jersey Task Force on Child Abuse and Neglect Conference, 2013)

In the United States in 2011, 5,100 children in the foster care system were U.S. citizens born to deported undocumented immigrant parents. From 2010 to 2012, 204,810 deportees were parents of U.S.-born children. According to a report by the National Center for Child Welfare Excellence, “For every two immigrants taken into custody, one child is left behind.” Quoting the Supreme Court case Plyler v. Doe, Lianne Pietro states:

…those who elect to enter our territory by stealth and in violation of our law should be prepared to bear the consequences, including, but not limited to, deportation. But the children of those illegal entrants are not comparably situated. Their “parents have the ability to conform their conduct to societal norms,” and presumably the ability to remove themselves from the State’s jurisdiction; but the children who are plaintiffs in these cases “can affect neither their parents’ conduct nor their own status.”

Especially in border states, the topic of illegal immigration spurs on hours of rhetoric and in-fighting, whether on the floor of the legislature or at home. While our politicians battle it out, however, something is forgotten:

The children.

Having done nothing wrong themselves, often times these children can find themselves suddenly separated from their parents by hundreds of miles without any warning. For the Montes family, this nightmare became a reality as husband and father Felipe Montes was detained and sent to another state one day after dropping his children off at daycare. His wife, pregnant, was unable to fully provide for the family in Felipe’s absence, and the state moved to terminate their parental rights and put the children in foster care. The Montes’ story is just one of many ways that children can find themselves drawn into the child welfare system due to complications with immigration.

The primary issue is this: When deportation results in a child entering the child welfare system, how can we best serve that child? Previously, FAFS has reported on the rise in kinship care across the nation thanks to the passing of the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008.

Embracing Undocumented Relative Caregivers

Among other things, this act specifically empowered relative caregivers and provided incentives for adoption – this is a direct result of the feedback of child welfare professionals indicating that kinship care could provide the best outcomes for children. When you pair the ongoing efforts in the United States to place foster children in kinship homes (that is, a home with a state-approved relative caregiver) with the child-displacing effects of deportation, it becomes clear that the situation becomes very complicated. If an undocumented child is left in the care of the state due to deportation, it’s possible that their relatives in the country, if any can be found, may also be undocumented. Retired Michigan Judge Donald Shelton, in an interview with Ann Arbor News in 2012, spoke to this specific conundrum:

To make the analogy, we wouldn’t allow a person who had an outstanding (criminal) warrant to be a guardian,” he said. “The reason is that we’re placing that child with someone who may be gone the next day. So that’s right, if they’re undocumented, then they’re not going to be allowed to be guardians because it’s not in the best interest of the children.

As a result, deportation events, culminating with the entrance of children into the child welfare system, can be a major burden on the community.

Some states have been prepared for this growing problem. For example, the Illinois child welfare code already specifically indicates that “Immigration status of a relative caregiver should not hinder the placement of a relative child in the home.” For other states, however, the situation can become more tenuous. In Arizona, for example, the issue is compounded by the presence of Mexican-born children.

In addition to the US-born children of deported parents, sometimes non-native children remain behind and get placed into the child welfare system. In order to meet the increasing needs of these innocent children who get overlooked in the process, Arizona lawmakers have begun funding initiatives to help act in the children’s best interests. Tuscon.com reports that “A local group of juvenile court judges, attorneys, child-welfare caseworkers and Mexican officials are working together to find possible solutions.” Other efforts include a new set of federal guidelines that “emphasizes that child-welfare agencies train employees to deal with such cases and provide appropriate services to families.”

Alongside Arizona, the Texas Child Welfare system has recently adopted similar avenues to assist undocumented immigrants in becoming kinship caregivers, including waivers to allow undocumented immigrants to adopt children.

According to Melanie Cleveland, division administrator of the state’s Division of Family Protective Services (DFPS), “It’s part of the whole philosophy of the agency: recognizing that children first and foremost deserve to be within their own family if there’s any possible way that they can be safe and have a permanent residence.”

Cleveland suggests that the partnerships with various faith-based organizations in the state has been a big help in recruiting more diverse families, which allows DFPS to place children into homes within their original communities and cultures. In the past, recruitment of Latino families had been a challenge for Cleveland: “Latino families I talked to were more likely to experience barriers in the process,” she told Fostering Media Connections. “If they wanted a bilingual social worker, they had to wait longer.”

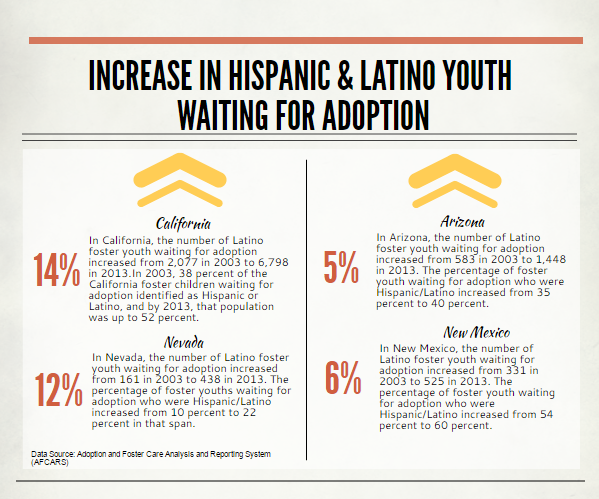

To help meet the needs of their communities, DFPS employed a large number of Spanish-speaking workers and translators. Such measures are crucial, especially as the number of Latino children in foster care grows. Citing the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System, the Chronicle for Social Change provides this helpful image to show how more and more Latino children find themselves awaiting adoption:

A study by AFCARS shows the increase in Hispanic and Latino youth awaiting adoption in California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico. New Jersey has experienced a similar increase.

New Jersey’s Progress

Efforts like those mentioned in Arizona, Texas and Illinois represent the first step of many needed to ensure positive outcomes for children, families and communities at large. Although not as close to the border as Arizona or Nevada, New Jersey’s foster care system does experience an influx of children from undocumented parents.

According to the Advocates for Children of New Jersey (ACNJ), the state has seen a similar increase in the number of Latino children awaiting adoption: From 2008 to 2012, that number rose from 14% to 19% of the total count of children waiting for adoption. Furthermore, with our proximity to major cities and relative population diversity, the state sees undocumented children coming from a variety of situations.

In one case study from the NJ Task Force on Child Abuse and Neglect (2013), DCF describes the story of a 14-year-old girl from Liberia who migrated here to escape a forced marriage to an abusive relative. In this case, the girl, Triana, came to the United States on a tourist visa with her mother, who then left her with a willing Liberian family in New Jersey. After a few years, Triana and her caregivers approached an immigration attorney to see if they can get her on the path to citizenship.

This story represents just one way an immigrant child may end up in the child welfare system without any particular fault of their own but, fortunately, New Jersey has a way to help this child find stability: the federally-based Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SJIS) law of 1990. This law helps undocumented youth obtain lawful immigration status by creating a classification for them so they can bypass traditional immigration laws that were intended for those entering the country illegally of their own volition. SJIS has had a number of modifications to its definition in the 26 years since its enactment. The current law, updated in 2008, defines a Special Immigrant Juvenile as:

An immigrant who has been declared dependent on a juvenile court located in the United States or whom such court has legally committed to, or placed under the custody of, an agency or department by a State, or individual or entity appointed by a State or juvenile court located in the United States, and whose reunification with 1 or both of the immigrant’s parents is not viable due to abuse, neglect, abandonment, or a similar basis found under State Law.

– 8 USC §1101(a)(27)(J); INA §101(a)(27)(J)

Moving Towards Positive Outcomes for the Children of Undocumented Immigrant

SIJS is just one way that New Jersey currently assists undocumented youths that find themselves in our state. In some cases, New Jersey even permits the use of a undocumented relative caregiver, provided it would be in the best interest of the child. As previously mentioned, states avoid placing children with undocumented relatives primarily because potential deportation (and thus the trauma of being placed back in care reinflicted) is a very serious risk. For New Jersey, according to section IV-A-11-200 of the DCF Policy Manual,

CP&P presumes that undocumented relative caregivers will have difficulty providing children in out-of-home placement with long or short term stability or permanency. Compelling justification is required to overcome this presumption and permit placement.

However, as with Texas, once compelling justification has been found and it is determined that placement with an undocumented relative caregiver is permissible, the new would-be kinship caregivers can file a waiver (located here) to bypass the rules that normally bar them from fostering.

The topic of illegal immigration can be loaded with distracting buzzwords and polarizing rhetoric, but at the end of the day, it is the many children in the United States, whether U.S.-born or not, who suffer most from the deportation process. Although a relatively new issue for the child welfare system in the United States, many states are making great strides in their ability to care for and provide the best outcomes for any children that find themselves within our borders.

Through enhanced cooperation with foreign entities like the Mexican Consulate, specific avenues built for undocumented children to enter the child welfare system and a greater willingness to place children with undocumented relative caregivers, states are slowly ensuring that these children do not need to have their lives violently disrupted by the actions of adults who they cannot affect.