The state of Oregon is under scrutiny for their treatment of youth in the child welfare system. One problem is Oregon’s continued reliance on congregate care facilities to house foster youth, even when these settings may not be appropriate.

Marking a national shift away from congregate care (group) homes The Family First Prevention Services Act (FFSPA) was approved in 2018 and will be implemented in October of 2019. This act functions under the understanding that for youth, prevention strategies and kinship care are less traumatic than being placed in traditional foster homes by implementing prevention strategies and support for kinship families.

In order to effectively implement the new laws, funds will be redirected from congregate care to prevention services. According to Casey Family Programs, congregate homes should be used to serve children with complex behavioral challenges, not to meet general placement needs. Of the approximately 437,000 children in foster care, about 53,000 reside in group facilities.

Allocating money for prevention is important but may cause difficulties for states that still rely heavily on congregate facilities.

Continued Congregate Care in Oregon

Oregon is one state that is struggling to move beyond congregate housing. After an audit and a lawsuit headed by the nonprofit A Better Childhood, the state has come under fire for their treatment of foster youth. According to Reuters, the lawsuit has been filed on behalf of ten youth in care whom Marcia Lowry, director of the organization behind the complaint, says have been revictimized during their time in the system.

Some individuals in the lawsuit lived in group home placements. After committing to stop housing youth in hotel rooms after a 2016 grievance, Oregon moved children into congregate care programs where they live in refurbished jail cells. The Youth Inspiration Program (YIP) in Klamath Falls houses adolescents in a repurposed wing of a functioning juvenile detention center.

A 16-year-old girl in the current lawsuit was confined to a cinder block cell at YIP and underwent daily therapy for sexual and substance abuse, neither of which she had ever experienced. An article by Sarah Zimmerman of the Associated Press explains that youth in these programs have been subject to strip searches, had little access to extracurricular activities and had limited contact with family members. Individuals with mild behavioral problems have ended up in programs like YIP even though these services are meant to house those with more severe physical and behavioral needs.

The state continues to rely on these facilities despite national efforts to move away from congregate care, and in February, Oregon governor Kate Brown requested a 12 million dollar increase in budget for YIP.

Oregon’s Systemic Problems

Oregon has a history of placing children in inappropriate housing, from refurbished jail cells and[hotel rooms to costly out of state facilities. The state says it is having difficulty finding family homes for youth and, according to the current audit, overburdened caseworkers, ineffective management and lack of resource parent retention are at fault.

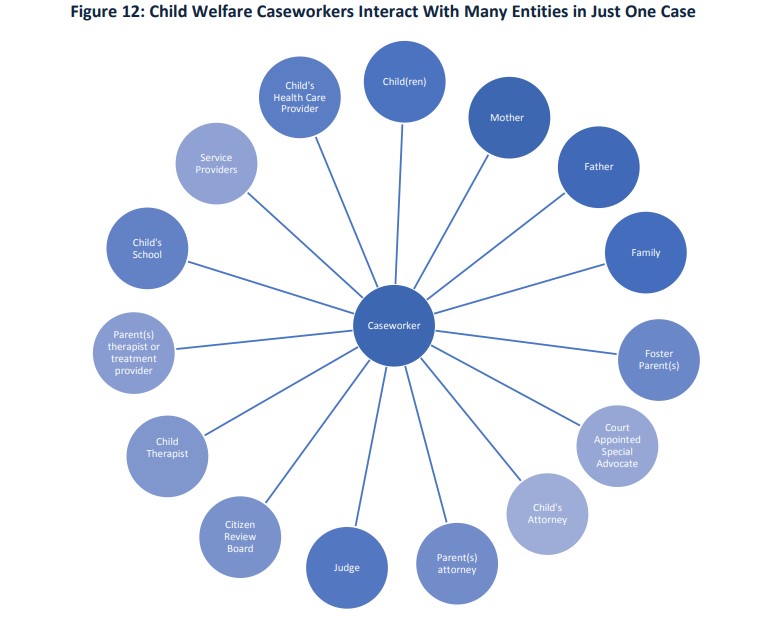

Overwhelming workloads are part of the problem. “Our current caseloads are more than double and sometimes approaching triple of what they should be,” said caseworker Rosanne Scott. Child welfare workers are expected to interact with multiple entities in each case, and handling double or triple the recommended workload makes them unable to perform their duties. Caseworker Bridget Rayburn told Oregon Public Broadcasting, “Someone cries at their desk every day. Not because of trauma. Because they’re overwhelmed with work.”

Constrictive workloads will also make it difficult to prioritize prevention strategies outlined by the FFPSA. Caseworker Kelly Scott told Oregon Public Broadcasting that she would love to be able to focus on prevention, but “because of our severe and chronic under-staffing, we don’t have the ability to work with a family in any meaningful way unless they are coming in our door through a pretty serious concern.” Without the means to administer prevention services, more children are removed from their homes and placed into the flooded child welfare system. Oregon DHS says it would need to hire more than 1,000 child welfare workers to reduce caseloads significantly.

Furthermore, ineffective management creates a system that is “disorganized, inconsistent, and high risk for the children it serves,” according to the audit. The administration cultivates “a culture of blame and distrust” where workers are afraid to make mistakes. Auditor Jamie Ralls, who worked closely on the Oregon audit, explains, “There’s a culture there of being afraid if you do something wrong, your head’s going to roll.” Child welfare workers’ demanding daily activities may be amplified by this type of work environment.

Beyond overburdened caseworkers and chronic mismanagement, Oregon does not have an effective strategy for the recruitment and retention of foster parents. The audit explains that the agency “struggles to retain and support the foster homes it does have within its network.”

New Jersey Prevention

As a leader in child welfare, New Jersey has emphasized in-home prevention services since 2004. As of September 2018, 41,945 children benefited from the use of in-home prevention strategies. From 2004 to 2018, the amount of children in out-of-home placements was cut in half, from around 12,000 to 6,225 children, with half of youth in care being in state-funded kinship placements.

New Jersey also creates a network of support for their resource families. For example, embrella provides family advocates, mentoring programs and Connecting Families[meetings to maintain a supportive community during the difficult times in the life of a resource parent.

New Jersey’s foster care system has had its own issues in the past. Former New Jersey Foster Care Scholar Stephanie Ahenkora’s placement in a shelter at age 17 echoes stories of YIP – it was a transitional home for foster youth leaving the juvenile detention center across the street. For Stephanie, a 17-year-old without any behavioral problems, eating meals at the detention center and being around peers who had experienced jail time was isolating. However, a 1999 lawsuit filed against New Jersey spurred positive change in the foster care system.

The brighter future created in New Jersey is possible for other states as well. According to Marcia Lowry, “It is possible to fix these systems, it’s just a lot of work. This forces the state to pay attention to the plight of these children.”

To read the Oregon child welfare audit, click here

For more details on FFPSA click here